Adam Rapp is one of those polymaths you read about. A playwright, novelist, musician, screenwriter, director, basketball player…

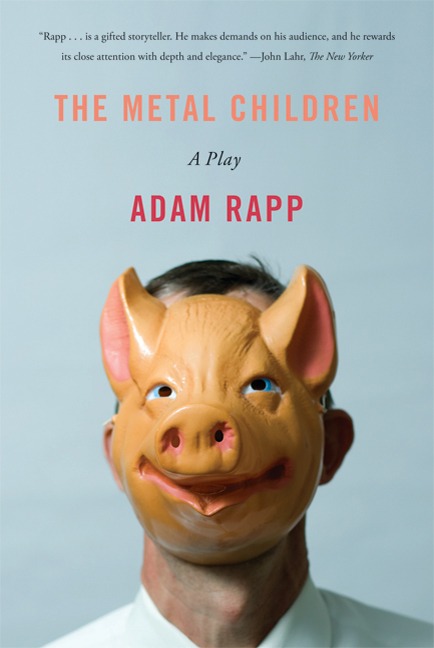

He’s written a couple dozen plays, including Pulitzer Prize finalist Red Light Winter (2006); The Metal Children (2010), which starred Billy Crudup in its New York premiere; and Nocturne (2001), an icy portrait of grief which prompted Variety to label Rapp one to watch “with keen interest”. His books fall into both the young adult and adult-adult categories. They include The Year of Endless Sorrows (2006); 33 Snowfish, a tale of sexual abuse that the American Library Association chose as one of its 2004 highlights; and Under the Wolf, Under the Dog (2004), which was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist and winner of the Schneider Family Book Award.

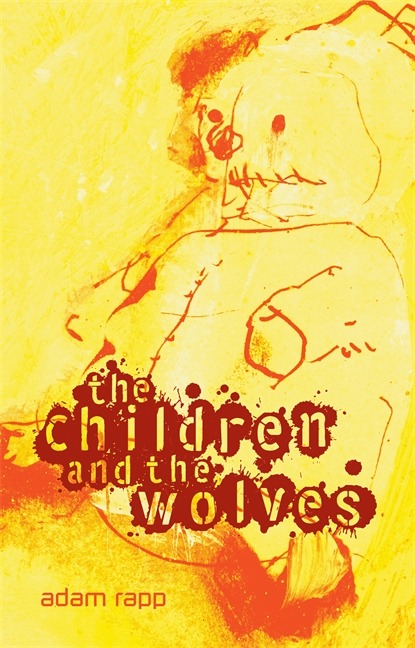

The Children and the Wolves, published in 2012, is a particularly intense brew. The writing is by turns visceral and tender. Take Wiggins, who emerges as the central character:

The Children and the Wolves, published in 2012, is a particularly intense brew. The writing is by turns visceral and tender. Take Wiggins, who emerges as the central character:

Sometimes I imagine myself in a pickle jar, floating in science juice. Barely alive with see-through skin. My heart like a little white raisin.

But later:

I imagine a soul is a little perfect crystal egg floating in your chest. Somewhere deeper than where they put your heart.

Wiggins is complicit in the kidnap of a three-year-old, I might add. Fortunately, he comes good: sickened by a moment of skull-mashing violence by his sadistic friend Bounce, he decides to free the child. It’s a Day-Glo fantasy of pharmaceuticals and neglect — almost Ballardian at times, but Ballard filtered through Palahniuk. Or Philip Ridley on speed.

I spoke to Adam this week about his work.

Charles Arrowsmith: You spent your adolescence in military school and playing basketball. How do you think your upbringing has directed your writing?

Adam Rapp: Well, for me, military school was an incredibly isolating experience. At 14 I was separated from my family, and thrust into an unforgiving system of relentless structure and discipline. And I deserved every second of it. I was a fuck-up. I was admitted late to school so I started out a few weeks behind all the other new boys, which immediately put me at a disadvantage. I was also small for my age. I was the runt of my freshman class. All this to say that I felt like an outsider, always looking in, trying to find my way in, and perhaps forced to form my own thoughts about things at a very young age. I think all of this led to wanting to write. Looking through a peephole at the rest of the world and having a lot to say about it.

Adam Rapp: Well, for me, military school was an incredibly isolating experience. At 14 I was separated from my family, and thrust into an unforgiving system of relentless structure and discipline. And I deserved every second of it. I was a fuck-up. I was admitted late to school so I started out a few weeks behind all the other new boys, which immediately put me at a disadvantage. I was also small for my age. I was the runt of my freshman class. All this to say that I felt like an outsider, always looking in, trying to find my way in, and perhaps forced to form my own thoughts about things at a very young age. I think all of this led to wanting to write. Looking through a peephole at the rest of the world and having a lot to say about it.

CA: Many of your novels fall into the bookstore category of “young adult fiction”. Is this a useful classification?

AR: Probably not. I don’t think parents take too well to my books — a lot of them are about kids railing against authority, their community, or themselves for that matter. The “Young Adult” market is controlled by adults, not by kids themselves, so there’s a lot of gatekeeping going on. There are many terrific, progressive librarians and teachers out there who champion and curate “difficult” novels, but there are also a lot of reactionaries who try to keep my books off of lists, away from their local bookstores and classroom shelves. I love the idea of teenagers reading my books — I hope they pass them around in secret — but I don’t think my “YA” stuff should necessarily be classified as such.

CA: Philip Roth wrote in American Pastoral about the “indigenous American Berserk”, a species of violence that’s emerged out of American culture that’s extreme, sudden, remorseless, sinister. I feel a lot of your work taps into this, especially The Children and the Wolves. What does the “American Berserk” mean to you?

AR: There seems to be this unarticulated expression of violence in our country. Teenagers are killing each other in high school cafeterias, gymnasiums, parking lots. I think it stems from the deepest, most cellular roots of consumerism. There is so much insane advertising imagery — sex, drugs, violence, the lunatic dreamscapes of masculinism, etc — that is attached to products of middle-class ascendancy. We are born into a culture of “want”. There is this fallacy that if we can acquire those sneakers, rock those jeans, or sport that high-end designer jacket, we will somehow be delivered to happiness. Americans are born into this contract with the world. It used to be catalogues and magazines and now it’s on our computers, our phones, and other devices that we curate ourselves so we can have easier access to making the perfect purchase. The perfect car and the perfect house and the perfect wardrobe and body perfection and anti-aging and on and on and on. For teenagers, this combined with the pressure to test well and have sex and satisfy parental legacy and NOT stray from the programme of success seems to breed a new kind of revolt. Teens are constantly told what NOT to read and what NOT to eat and what NOT to do with their free time. They are rarely taught to actually question things, but rather forced to accept traditions of curriculums, aptitude testing, athletic excellence, etc. The relationship between young people and the possibilities of a future American life are grim. We are starting to destroy ourselves. Kids are literally aiming our own guns at other kids in what is supposed to be the most civil, intellectually progressive context of American life — the education sector. There is a savage animalism that is starting to emerge in younger and younger ages. Perhaps there is a perverse lack of balance in American life, a profound lack of questioning our own methods — we’re the greatest nation in the world after all! (Sorry for the cynicism…)

CA: Your play The Metal Children seems to confront your own experiences with censorship. [Adam’s 1997 novel The Buffalo Tree was banned in a Pennsylvanian high school in 2005. The New York Times reported]. Do writers have responsibilities?

CA: Your play The Metal Children seems to confront your own experiences with censorship. [Adam’s 1997 novel The Buffalo Tree was banned in a Pennsylvanian high school in 2005. The New York Times reported]. Do writers have responsibilities?

AR: Yes. Whether it be through fiction, journalism, film, TV, theatre, whathaveyou, our responsibility is to attempt to tell the truth as artfully, intensely, and humanely as possible. Sometimes this requires expressions of brutality, sadness, violence, or lunacy. The best writers don’t shy away from darker terrain. There is incredible eloquence and pain in great writing. Entertainment is fine, as is humour — both are essential to storytelling — but those who are merely aiming to give pleasure through writing should sell pantyhose and cupcakes.

CA: You’ve worked a lot in different media: film, music, TV, theatre, novels… Do you feel the need to change it up? Do you write where the work is? Do your ideas, when they arrive, come pre-packaged in a particular form?

AR: The crossing over started to happen in my early thirties when I realized I couldn’t stay solvent by just writing fiction and plays. I started out writing fiction. When I was still in college I began my first novel. I wanted to be a novelist — it’s why I moved to New York. But then through exposure to Off-Broadway I got bemused by theatre and started trying to write plays. And then things went well on that front for a while so the West Coast came calling. I resisted some opportunities but ultimately started writing and directing film and writing for TV. The money is good in TV. And the writer in the TV world has tremendous power. The money should be that good for fiction and theatre too, but it’s just not.

CA: What are the last three books you read?

AR: Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad, Light Years by James Salter, and John Heilpern’s biography of John Osborne.

CA: Thanks, Adam!

Adam Rapp will appear at our next Seriously Entertaining show, Falling for Perfection, on June 23. You can buy tickets on the City Winery NYC website. Be sure to follow Adam on Twitter.