The SpeakEasy Bookmobile on Juneteenth Weekend

On my first outing with the SpeakEasy Bookmobile, I was told to expect the unexpected when it came to the types of books people might find appealing. I was happily surprised by what I witnessed on my first of two days with the truck. For starters, I had assumed that the small pile of math reference books that SpeakEasy has accumulated would not receive much traction — until a beaming young woman approached us and specifically requested them. Reading tastes were varied:

“Do you have any how-to photography books?”

“I’m looking for something on metaphysics.”

“Historical fiction, like maybe about the Mona Lisa.”

Also, to my joy, poetry books I placed prominently on the truck’s shelves were scooped up — a bilingual edition of Cesar Vallejo’s collected poems; The Kissing of Kissing by Hannah Emerson (whom I had the great pleasure of seeing at the Poetry Project in late May); and Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic.

Last month’s Juneteenth weekend saw the Bookmobile loaded up with piles of book donations and hitting the streets in multiple boroughs. On Saturday and Sunday, July 18 & 19, we visited the John Adams Houses in the southern Bronx neighborhood of Woodstock on one day, and followed up on the next day with an afternoon spent at the Brooklyn Museum in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. In each location, we distributed hundreds of free books, all brand new titles to visitors that included families, artists, writers, and the random passers-by.

The weekend presented an opportunity for educators, parents, teenagers, children, artists, and writers to come together to commemorate the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Both days were promoted as Juneteenth celebrations and featured a mix of art-making, food, dance, and more. The Bookmobile was welcomed by visitors young and old alike, each offering smiles and words of thanks:

“This is really dope.”

“Thank you very much for being here.”

“My kids will love this.”

“Where can we find you next?”

Their comments were heartening, as was the sight of young people’s hands reaching high for titles on the truck’s shelves — Chlorine Sky and Operation Sisterhood, both titles from YA writer Mahogany L. Browne, were in high demand, as well as Operation Sisterhood by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich. Adults found titles that spoke to them, too, from Buki Papillon’s An Ordinary Wonder, to Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, to Colson Whitehead’s The Intuitionist.

Amidst the celebrations, the weekend called for quiet reflection as well, eliciting comments from visitors in Woodstock and Crown Heights. “I’m waiting for my granddaughter,” Maria Crespo, a middle-aged woman with a kind smile, told me in The Bronx. She was standing beside the Bookmobile on 152nd St. “The library at Southern Boulevard and Tiffany has been closed for months.” She continued: “My granddaughter is seven. She’s always watching me and her mom because we’re always reading.”

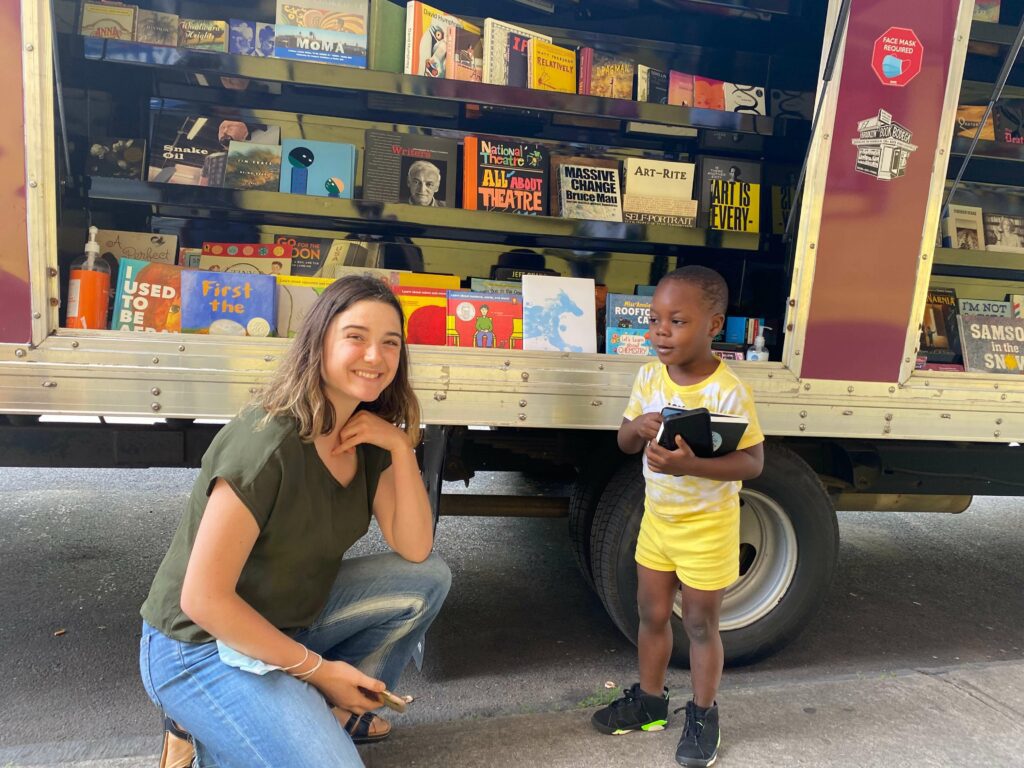

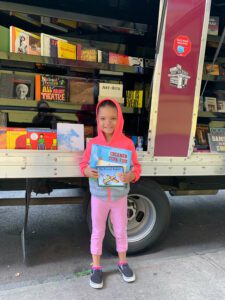

The lack of book culture for youth in The Bronx is often bemoaned, but on the day we visited, childrens’ books were flying off the shelves all day long, as kids piled free books in their arms, including such titles as Laura Vacaro Seeger’s elegant picture books Lemons Are Not Red, Blue, and Dog and Bear, Philip C. Stead’s Creamed Tuna Fish & Peas on Toast, and Frank Le Gall’s Rooftop Cat. I kneeled down to meet the eyes of a four-year old boy and together we turned the pages of a small Roaring Book Press publication, about a friendship between a rabbit and a mouse. I asked him to identify the different animals as we flipped through it together, and he answered without hesitation: “rabbit!” “mouse!” “elephant!”

Six-year-old Renesme of Woodstock, The Bronx, with her pick of books — including the Caldecott-winning My Friend Rabbit.

On Saturday, in front of the John Adams Houses in The Bronx, a street festival took shape near the Bookmobile featuring an assortment of food vendors, art installations, and a DJ at which young children giggled and swayed. There was also a table dedicated to art projects for kids, overseen by ArtBridge, SpeakEasy’s partner for the day. Here, ArtBridge’s Program Director Jon Souza, a young man with a gentle demeanor, led a small group of children — some already with books plucked off the truck in hand— through simple art activities. Souza grew up in Harlem and has established himself as a graffiti/mural artist and musician. He’s also a practiced arts educator and cultural ambassador with a Master’s degree from Columbia in advanced management and finance. Unsurprisingly, he seemed highly sensitive and attuned to those around him, as well as highly competent and organized.

A nonprofit that aspires, as House of SpeakEasy does, to provide access to books and book culture to communities that are traditionally underserved, the organization finds a common sense of purpose with other nonprofits doing complementary work. Souza has clearly devoted significant time to the issues of how best to provide access to the arts: “Art that connects to a social value or social issue, that’s my thing. That’s kind of what brought me to ArtBridge, you know. Thinking about, How do I come into a community to make sure it’s actually culturally relevant, that there’s actually a strong impact that speaks to the community? How do I make sure I reach that voice and make sure it’s represented?”

ArtBridge’s mission has, since its inception in 2008, centered on creating public art, primarily on sidewalk sheds and scaffolding. More recently, they’ve partnered with the New York City Housing Authority—which is also a SpeakEasy partner—to commission installations from 59 artists at 16 different NYCHA sites, with support from Mayor Eric Adams. “Our hope is also to make sure, with the community, that it’s a collaborative, creative process, so every program, every center has 3–5 workshops, run by the artists, where we invite in the community — community centers, senior centers, resident associations.”

For Souza, the mobilization of public art carries particular import in times of widespread social upheaval: “I think especially after the pandemic, it was a time for the creators. People didn’t know what to do, and now, especially with the youth, public art needs to be out there. And people respond to it, and the impact is visible.” He looked back down at the table in front of him, which was lined with a wide sheet of drawing paper on which children were coloring: “When we talk about equity, how do we bring up artists who are street artists for real? They don’t have an MFA, they might not have a college degree, but they’re really amazing. They really have their ear to the street, and they have a connection to the community. There’s a different kind of value there, you know what I mean? There’s always a question of how we can actually be with the community, and the people who are actually from the community.”

On the same day in The Bronx, I met Vernon “Chip” Turner, Jr., a resident of the Adams Houses. Turner was dressed brightly — a red baseball cap facing backwards with matching red apron, gray jeans rolled up to the calves, true white socks and Nike sneakers, and a smart mahogany corduroy coat. An artist, painter, photographer, carpenter, and writer, Turner had been waiting by a table we had set up, flipping through a selection of oversized art books and commenting on the pieces he liked or knew. He’s 67, he told me — “I’m 66 — no, I’m 67. I keep making myself younger” — and grew up in The Bronx. His father was also born in New York, and his mother in Chicago. Energetic and engaged, he speaks in starts and with a lisp. When I asked to record our discussion, he said, “Sure, but you won’t be able to understand me. I have different personality traits,” he explained. “So I need to calm down.” What helps with the condition? Art, lots of it, and community engagement. “My program is called PROS [Personalized Recovery Oriented Services]. I go there and we do different things — art, poetry. I do that now. It’s the therapy for me. … Art, poetry, people, writing poems about people. I try to sketch them. This is what helps me out, relaxes me.”

I asked him what he wished he saw more widely around his community now. His response: “I think people should make their own books, like tiny books and poetry, with drawings on the front page. … Like you’re interviewing me, I think that they need to be interviewed, too.” Also: basketball. We were standing next to a court as we spoke, and he gestured towards it: “I sit right there on the bench where they have music, and I watch the kids, I cheer them on, I say, ‘Get fancy on ‘em!’, ‘Shakin’ ‘em up.’ Yeah. I like kids that like to express themselves. I like little ones.” As he spoke, I was moved by his evident dedication to his people. During our conversation, he stopped periodically to speak to passers-by, adults and children alike: “Okay, you take care now! May God bless you and may you live a long time! Give back to the community for a long time, alright?”

In the end, what did I feel throughout the Juneteenth festivities? Joy, for certain— a celebration of community and the excitement of putting books in readers’ hands. But also a sense of collective anxiety — hearing residents speak of recent violence on their streets, soaring food costs, and relatives ill from the continuing pandemic. Again and again, however, I saw individuals’ commitment to the neighborhoods they call home: in a woman’s determined search for a book for her granddaughter; in the granddaughter’s excitement to crack open that book; in families’ willingness to come out for the festivities while gun violence is on the rise in the city and the country. In all of this, I was reminded of the memoir On Juneteenth by Dr. Annette Gordon-Reed, Harvard Law Professor, historian, and Pulitzer Prize–winning author. Discussing her relationship with her birth-state of Texas, she wrote: “When asked, as I have been very often, to explain what I love about Texas, given all that I know of what has happened there — and is still happening there — the best response I can give is that this is where my first family and connections were. Love does not require taking an uncritical stance toward the objects of one’s affections. In truth, it often requires the opposite. We can’t be of real service to the hopes we have for places — and people, ourselves included — without a cleareyed assessment of their (and our) strengths and weaknesses.” To look, and to look, and to look (to keep our eyes open). To love. And, perhaps, to be of service. As the Bookmobile moves ahead with a summer of community outreach, I hope to learn and practice these values. To uplift, as “Chip” put it, the “art, poetry, people” at the center of each outing.

Ryan Tuozzolo is a writer living in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and a Book Specialist for House of SpeakEasy. You can reach her at [email protected].