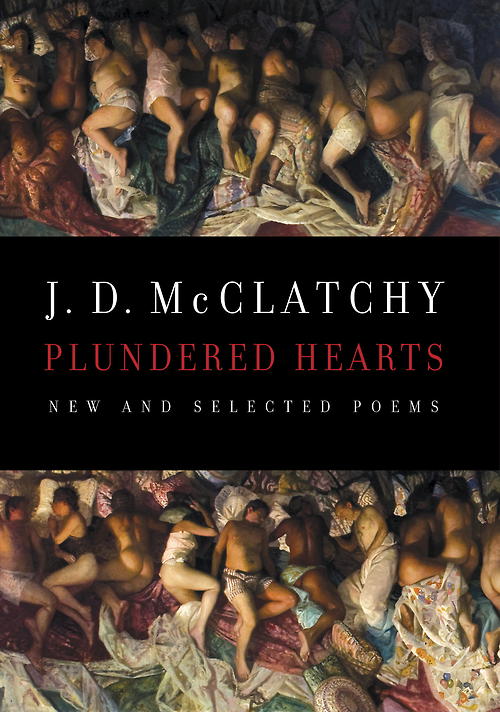

Honouring J.D. McClatchy in 1991, the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters stated, “It may be that no more eloquent poet will emerge in his American generation.” Since then, his reputation has grown as exponentially as his output. A poet, essayist, librettist — and Professor of English at Yale — McClatchy is certainly one of the hardest-working poets in America. Knopf has kindly published a new collection of his work, Plundered Hearts: New and Selected Poems, providing readers with a perfect introduction to his world.

Honouring J.D. McClatchy in 1991, the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters stated, “It may be that no more eloquent poet will emerge in his American generation.” Since then, his reputation has grown as exponentially as his output. A poet, essayist, librettist — and Professor of English at Yale — McClatchy is certainly one of the hardest-working poets in America. Knopf has kindly published a new collection of his work, Plundered Hearts: New and Selected Poems, providing readers with a perfect introduction to his world.

One of the new poems, “Prelude, Delay, and Epitaph”, is as good a way in as any:

A finger is cut from a rubber glove

And cinched as a tourniquet around my toe.

The gouging ingrown nail is to be removed.

The shots supposed to have pricked and burned

The nerves diabetes has numbed never notice.

The toe, as I watch, slowly turns a bluish

Gray, the color of flesh on a slab, the size

Of a fetus floating on the toilet’s Styx,

But lumpen, the blunt hull of a tug slowly

Nosing the huge, clumsy vessel into port.

McClatchy continues; this is just the “prelude”. But there is much even in this fragment that is typical of his precise and visceral style. First, subject matter. Many of the new poems in Plundered Hearts — “Kiss Kiss”, “My Robotic Prostatectomy”, “His Own Life” — and a fair chunk of the old (“Cancer”, “My Mammogram”) are carnal, bloody, clinical. Also, form. McClatchy is a surgeon-poet, versifying with a scalpel. He often marries traditional poetic forms with taboo or unpleasant subjects. (“Cancer”, for instance, comprises three sonnets.) “An elegant, elaborated format helps tame the taboo,” he told The Paris Review in 2002, “and a stark subject — feces, say, or cancer, or the penis — charges the poem’s formal energies with an unexpected drive.”

Here, the precise syntax of the first half of the stanza gives way to enjambment, the sticky consonants of “toilet’s Styx”, and the dull slow rhythm of “lumpen”, “blunt”, “hull”, “tug” in the second. The enjambed “bluish / Gray” mimics the changing colour of the afflicted toe just as the bulging lines (mostly eleven syllables after line 1’s neat ten) hint at the matter that should be excised. It’s as if the “gouging ingrown nail” is lodged in the poem itself. These subtler effects, combined with the rather gruesome imagery — “flesh on a slab”, “a fetus floating” — have a powerfully nauseating effect.

This poem is the latest in a long line of carnal efforts. As he told The Paris Review, McClatchy is fascinated by the body:

In a sense, I’ve merely come to agree with George Seferis who once said that the poet has only one subject: his own living body. It is the body where we learn our first lessons in pain and pleasure, and our later lessons in betrayal and decay.

“My Mammogram”, from the 1998 collection Ten Commandments, is one of the strongest expressions of this betrayal. In it, when the narrator discovers that something might be wrong with the “too tender skin” of his breasts, his body is transformed by affect, as are his surroundings: “The nurse has an executioner’s gentle eyes”; “The room gets lethal”. DNA, which contains the secret code of life, also hides the clues to mortality, and despite his classical leanings, for McClatchy the question of fate is not one of divinities but of genes: “the future each of us blankly awaits / Was long ago written on the genetic wall”. The body’s betrayal is in becoming what it was always going to: grotesque, a crucible of pain. In the final stanza:

So suppose the breasts fill out until I look

Like my own mother … ready to nurse a son,

A version of myself, the infant understood

In the end as the way my own death had come.

Or will I in a decade be back here again,

The diagnosis this time not freakish but fatal?

The changes in one’s later years all tend,

Until the last one, toward the farcical,

Each of us slowly turned into something that hurts,

Someone we no longer recognize.

If soul is the final shape I shall assume,

The shadow brightening against the fluorescent gloom,

An absence as clumsily slipped into as this shirt,

Then which of my bodies will have been the best disguise?

How can the body, mutable as it is, truly be the temple of the soul?

McClatchy’s work is rich and dense and muscular and repays close reading. But that’s not to say it’s not also fun, animated by a humour as rigorous as its flipside solemnity. In Plundered Hearts you’ll find poems about Renoir’s La Règle du Jeu (“An Essay on Friendship”), “Auden’s OED” (as it sounds), and bees (“Bees”). Take the dark humour of this passage from “Lingering Doubts”:

The woman giving birth

Was standing near a bed,

The child apparently worth

The risk that lay ahead.

“Don’t be stubborn. Here,

Lie down,” he crossly said.

She winced and shook her head.

“Spoken just like a man.

Lie down? A bed? That’s where

The trouble first began.”

Indeed, in one of his other careers — as a librettist — McClatchy is well known for his witty English-language librettos to some of Mozart’s airiest, most delicious operas, collected in Seven Mozart Librettos.

For further reading, The Paris Review‘s fascinating 2002 interview with McClatchy can be found in full here.

J.D. McClatchy, who has also edited The Yale Review for more than twenty years, joins the House of SpeakEasy on April 28 for “In Case of Emergency”. You can buy tickets here.