Olives

Olives

by A.E. Stallings

TriQuarterly Books, 2012; 80pp

The poems in Olives are smart yet accessible; beautiful but deadly; both tragic and humorous. In her third collection, following Archaic Smile (1999) and Hapax (2006), poet A.E. Stallings playfully blends ancient and modern, Persephone and Barney (yes the cute purple dinosaur), with strangely profound results. The collection’s four parts bear the faint imprint of overarching narrative: lovers flirt and argue; chaos and death threaten; redemption of sorts is found in offspring (though perhaps not in The Offspring, as the poem “Pop Music” wryly points out). The classical world makes for an atmospheric backdrop. Stallings, as most bios will tell you, moved from Athens, Georgia, to Athens, Greece, and the influence of all those ruins tells. But the modern persistently intrudes, not least in the form of the telephone, which, it’s suggested, is a sort of twenty-first-century deus ex machina (certainly a machina). “At any hour, the future or the past / Can dial into the room and change our lives,” writes Stallings in “Telephonophobia,” a poem placed in suggestive contiguity with one actually called “Deus Ex Machina.” One could hardly invent a Greeker-looking word than “Telephonophobia,” even if its provenance is incontrovertibly modern. And it’s this punning blend of past and present that’s the source of much that’s pleasurable in Stallings’ poems. Not for nothing was Olives a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

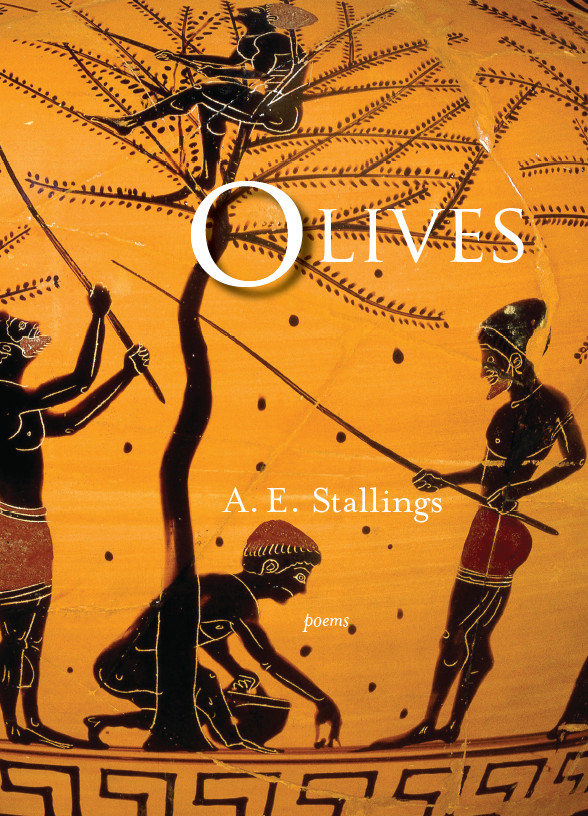

We find this elision between the ancient and the modern in the very first poem, where the eponymous fruit is pictured “on spears / Of toothpicks maybe, drowned beneath a tide / Of vodka and vermouth.” The enjambment after “spears” crosses a verse break — a division we might also read as historical. The book’s cover depicts an amphora painted with a scene of olive gathering, so one perhaps expected Grecian frolics; cocktail hour less so. The erotic has not been lost in the passage to the present, though; the commingling of colors in Stallings’ description of the olives — “Brown greens and purple browns, the blacks and blues / That chart the slow chromatics of a bruise” — is gorgeous, perhaps especially in its hint of violence. (Sex and death are, of course, bedfellows throughout.)

The poems in the first part of the book, “The Argument,” are among my favorite. Simple and elegant, they’re also often quite breathtaking. In “Sublunary,” our lovers bear witness to a lunar eclipse. The poem’s first word, “Midsentence,” captures perfectly the arresting spectacle, “sweeping like a wing across that stark / Alien surface at the speed of dark.” And gosh, what an image, “speed of dark”: sinister, contradictory, deadly. It must be both perceptibly slow, “sweeping like a wing,” yet simultaneously, in celestial terms, inconceivably fast.

There’s darkness, too, in “The Argument” and “Burned,” which occur towards the end of Part I. In the former, a lovers’ spat takes on epically violent overtones: “It was as if, out of the undergrowth, / They stepped into a clearing and the sun, / Machetes still in hand.” As a consequence of their fight, “both were suddenly afraid / And there was no one now to comfort them.” And for good reason, for in “Burned” we are told, over and over, that “You cannot unburn what is burned.” The repetition of this phrase takes on an incantatory air; it’s as if a witch has materialised out of nowhere to chide our lovers. “You longed for home,” she says, “but while you yearned, / The black ships smoldered on the coast; / You can’t go back.” The Homeric reference is telling: as it was for Ulysses, it’s impossible for them to truly return home. “It’s time you learned,” they’re told, “That what is burned is burned is burned.”

Stallings isn’t averse to fun, though. This is, after all, a poet who took on Lucretius “for a lark” (see the textual note to her lucid translation of The Nature of Things) and in so doing successfully sidestepped “a fusty pose of Thees and Thous.” In the classically themed third part of Olives, she meditates somewhat irreverently on the adventures of the unfortunate beauty Psyche. Of Cerberus, the Underworld’s watchdog, she remarks, “The sorry hound is usually sleeping / (Three heads, no brain).” When Psyche meets Persephone in that same Underworld — apparently in a bar — the latter comments, “This place is dead — a real dive.” Later, in the collection’s most obviously comic poem, “Dinosaur Fever,” dedicated to her argonaut-son Jason, Stallings writes:

Tots tell you what things mean in Greek,

In tones superior and mammalian;

It seems they only just learned to speak

And now they speak sesquipedalian.

Many of the poems are in whispered conversation with each other. “Four Fibs,” with its Edenic setting and Eve-tempting “snake-oil salesman”, foreshadows its successor, “The Compost Heap,” which ends in somewhat metaphoric fashion for our lovers:

We left the garden in the fall —

You turned the heap up with the rake

And startled latent in its heart

The dark glissando of a snake.

Similarly, the telephone introduced in “Telephonophobia” calls back in “Fairy-Tale Logic,” and the eclipse from “Sublunary” is eerily echoed in “Hide and Seek,” when the poet’s son pretends to be a shadow (“it chilled me a little, / How still he stood, giving darkness his shape.”) These through-lines give the collection a pleasing coherence even when the subject matter and verse form vary so much. Even the sublime terror that lurks in the earlier poems is reprised in the lighter Part IV. In “Listening to Peter and the Wolf with Jason, Aged Three,” the child asserts, “with grave logic,” “The wolf is in the music”:

And so it is. Just then, out of the gloom

The cymbal menaces, the French horns loom.

And the music is loose. The music’s in the room.

Animals, music, pity and fear. We’re in distinctly Greek territory, as indeed we are throughout Olives. Fortunately for Stallings, though, the only violence at the end of her story is in the pages of the fairy-tales she reads her son.

You can buy Olives at Barnes and Noble. A.E. Stallings will appear at our next Seriously Entertaining show, No Return, on March 9 at City Winery NYC. Buy your tickets here.