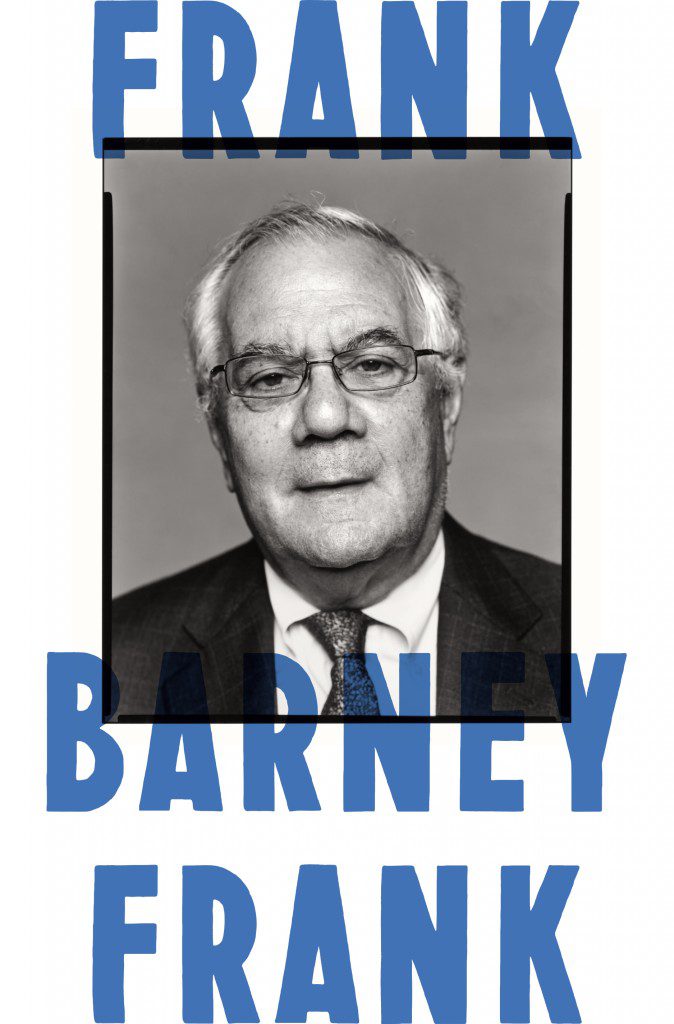

Frank: A Life in Politics from the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage

Frank: A Life in Politics from the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage

Barney Frank

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015; 400pp

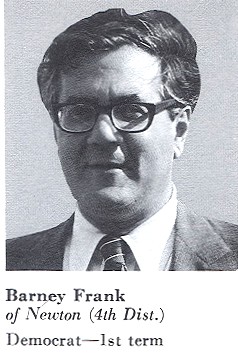

“In 1954, I was a fairly normal fourteen-year-old, enjoying sports, unhealthy food, and loud music,” writes Barney Frank at the start of his zippy, witty memoir. “But even then I realized that there were two ways in which I was different from the other guys: I was attracted to the idea of serving in government and I was attracted to the other guys.” These two tendencies — towards public service, towards men — are the organizing principles of Frank: A Life in Politics from the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage, which traces the activist Congressman’s career from his childhood in New Jersey through his thirty-two-year career representing Massachusetts in the House of Representatives. Along the way, we witness Frank’s efforts on behalf of the LGBT community during the AIDS crisis, we hear the true story of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”, and we see the financial crisis from the perspective of the man who lent his name to the biggest finance reform act in living memory.

The yardstick for Frank’s half-century of service is the contrast between the America of his youth and the one we live in today. In 1954, you couldn’t get a security clearance to work for the US government if you were gay, and The New York Times thought little of using the epithet “pervert” to describe you. In 2012, when Frank married Jim Ready — to whom this book is dedicated — he became the first member of Congress to marry a same-sex partner while in office. So far so good, and though he’s humble throughout, it’s clear that his advocacy went a huge way towards winning the necessary freedoms LGBT Americans have today. But as support for LGBT rights has increased over the last sixty years, so popular confidence in the US government — the belief, even, in its right to govern — has shrunk. In the 1950s, the Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower was able, in the Interstate Highway project, to institute one of the largest public works programs in US history. In recent years, Tea Party Republicans have been vocal critics of all forms of government activism, even when it has sought to ameliorate the after-effects of the global financial crisis. Frank’s faith, though, is unabated, and his perspicacious analysis of these two contrasting trends, and his marked hope for the future, are what gives Frank its particular authority and welly.

Barney Frank entered Congress the year Ronald Reagan became president. “I had arrived at the party,” he remarks wryly, “just when the curfew went into effect.” The curfew to which he refers is a metaphor for the precipitous decline of activist government in the Reagan era and since. Reagan’s belief that government was not the solution but rather the problem would come to characterize the philosophy of many Republicans and much of the electorate in the decades that followed his election. Not so Frank’s, though. He remains adamant that this “government stinks” attitude works against the needs of many who espouse it, including government critics on the left and the white middle- and working-class men who have fallen prey to the growing inequality of the last forty years or so:

Barney Frank entered Congress the year Ronald Reagan became president. “I had arrived at the party,” he remarks wryly, “just when the curfew went into effect.” The curfew to which he refers is a metaphor for the precipitous decline of activist government in the Reagan era and since. Reagan’s belief that government was not the solution but rather the problem would come to characterize the philosophy of many Republicans and much of the electorate in the decades that followed his election. Not so Frank’s, though. He remains adamant that this “government stinks” attitude works against the needs of many who espouse it, including government critics on the left and the white middle- and working-class men who have fallen prey to the growing inequality of the last forty years or so:

The first group is numerically less significant but is important in shaping the national dialogue. Even though most of its members continue to vote in a progovernment fashion, their efforts often work against the results they seek… Too often they fail to differentiate between a government that is hamstrung by its conservative critics and the actions of those critics themselves, which have created the problem.

In my view, white men reject activist government not because they reject a major role for the public sector but precisely because they support one — implicitly, perhaps, but nonetheless strongly — and have been punishing government for its failure to fulfill that mission. In one very important respect, the 1992 Clinton campaign mantra, “It’s the economy, stupid,” was even truer than its chanters realized. Where middle- and working-classes white males are concerned, the issue was not simply the importance of recovering from the recession of 1990-1991 but also the need to slow — and ultimately reverse — the steady erosion of their economic status that began in the mid-1970s and continues today.

Frank calls this growth in inequality “the great frustration of my political career”. For him, the solution lies in giving government the resources needed to meet the expectations the people have of it. How can this be done without raising taxes on the middle class? Simple: cut military expenditure and end the use of criminal penalties for drug users. “They are both twofers — they save money not by cutting back on things we should be doing, and from which society benefits, but by reducing expensive government activity that often does more harm than good.” Where you stand on these proposals probably depends on your political stance, but Frank argues his case powerfully, and it’s hard to deny his logic.

For many, especially in this nationwide month of Pride, the joy of reading Frank is going to lie in the passages tracing his extraordinary rise as an out-and-proud politician. Even before he came out publicly, Frank used his growing influence to fight for LGBT causes in Congress, which in the 1980s included the overturn of sodomy laws and the repeal of an immigration statute that expressly forbade “people afflicted with ‘psychopathic personalities’ and ‘sexual deviation'”, in other words LGBT immigrants, from entering the US either as visitors or permanent residents. His activism continued in the 1990s: it wasn’t until 1995 that President Clinton overturned, by executive order, the refusal of security clearances to LGBT staff in the federal government. Indeed, reading Frank is a reminder of both how far we’ve come and how recent it was that things were much worse.

It’s a cliché to say of Barney Frank that he lives up to his name, but nonetheless true. Indeed, the compulsion to be frank is what led him to become the first congressman to come out of his own volition. “The strain of living in the closet takes a heavy toll on your personality,” he remarks, and by the mid-80s he’d had enough: “I was tired of having to desex my pronouns, ration my visits to places I wanted to be, and avoid dancing with another man anywhere I might be photographed.” When he came out, over Memorial Day weekend in 1987, he recalls a Cirque du Soleil performance he attended in Boston where his presence was cause for a greater ovation than had been accorded to the Superman actor Christopher Reeve, also present. It’s one of many moving moments in this book that track the progress of LGBT acceptance in the US.

The progressive march has been a slow one, and Frank’s book is full of near-legislation. But he remains adamant that the legislative route is best, even when, as it often does, it involves deleterious compromises. Bill Clinton’s infamous “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” proposal, which Frank naturally disparages, grew out of a proposal he had himself made that would have allowed LGBT military personnel to continue to serve so long as their orientation was not advertised in the barracks. (DADT, of course, entailed dismissal of the found-out.) Though not undeterred, Frank used the passage of DADT as leverage to convince President Clinton to revoke the ban on security clearances. Clinton also urged the then attorney general to include persecution for sexual orientation or gender identity to the list of those eligible for refugee status. What’s more, Frank was able to intervene to prevent the appointment of the homophobic Samuel Nunn as Clinton’s secretary of state. This whack-a-mole approach to getting things done was part of what made him such a successful legislator.

He’s also blessed with a humor all too rare in politicians. When Reagan, who opposed abortion, introduced a budget cut for funds for pregnant women and disadvantaged children, Frank quipped that he “apparently believes that from the standpoint of the federal government, life begins at conception and ends at birth.” Quoting Robert Reich’s description of his own “nasal yell”, Frank concedes its accuracy by admitting “I long ago realized that it would be unwise for me to try to make anonymous phone calls.” Often humor is necessary just to get by. The Troubled Asset Relief Program, which Frank defends on the grounds that it “staved off total economic collapse and did not end up costing taxpayers”, nevertheless remains “the most wildly unpopular highly successful major program in America’s history”. It’s useful to have a sense of the absurd.

Barney Frank is a refreshingly candid and humble writer, and Frank is a heartening read. It is to his credit, and to the benefit of future generations, that Frank was able to overcome what seemed an insurmountable electoral handicap, and set about fighting, tenaciously, tirelessly, for improvements in the lives of others, even when his own seemed less than perfect. But lest you despair, it’s worth, on reaching the end of the book, rereading its dedication, which is its own happy ending: To Jim, who made “better late than never” my all-time favorite cliché.

Barney Frank recommends:

- Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.: The Political Biography of an American Dilemma, by Charles V. Hamilton (Simon & Schuster, 1992)

- The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Vol 3: Master of the Senate, by Robert A. Caro (Knopf, 2003)

Follow Barney Frank on Twitter: