I’ve never been psychoanalyzed… I’ve never even consulted a psychiatrist… I work out all my problems in my work.

— Truman Capote

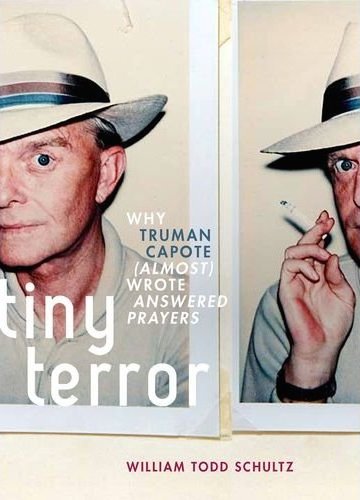

By the time Capote died, at the age of fifty-nine in 1984, years of substance abuse had shrunk his brain. His last completed book was In Cold Blood eighteen years previously. A heavily trailed follow-up, Answered Prayers, appeared in fragments so poisonous that the Park Avenue ladies whose adoration he’d cultivated for so long made a mass exodus from Mount Truman. His later years were characterised, in the words of William Todd Schultz, by “Studio 54, cocaine, prescription pills, Stoli vodka in an unmarked glass”. In a disastrous and notorious TV interview with Stanley Siegel, an evidently fried Capote confessed that his problems with alcohol and drugs would mean that “eventually I’ll kill myself… without meaning to…” Shortly before his death, he bought a one-way ticket to Los Angeles, knowing that his time was short. He died in the arms of his friend Joanne Carson. Schultz’s psychobiographical Tiny Terror: Why Truman Capote (Almost) Wrote Answered Prayers (Oxford University Press, 2011) puts Capote’s spectacular implosion under the microscope, finding in his early life the blueprint for his early death.

Answered Prayers was in many ways a lifelong project. Near the start of Douglas McGrath’s 2006 movie Infamous, we see Toby Jones’s Capote — in the 1950s — writing the title at the top of a blank page, although for the time being he gets no further. At around that time, he wrote to his editor, Bennett Cerf, of

a large novel, my magnum opus, a book about which I must be very silent, so as not [to] alarm my “sitters” and which I think will really arouse you when I outline it (only you must never mention it to a soul). The novel is called, “Answered Prayers”; and, if all goes well, I think it will answer mine.

— see Too Brief A Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote, ed. Gerald Clarke (Vintage International, 2005)

Schultz sees in Answered Prayers and its fallout a synthesis of the metanarratives of Capote’s life. The hooks he hangs his theory on are based in formative early experiences, what he calls “the life story writ small”.

As an adult, Capote often told tales of being abandoned in his childhood. There’s little reason to doubt these: his father, Arch Persons, really did up sticks, while his mother, Lillie Mae (later known as Nina), left him for long periods of time in the care of aunts. These experiences left the young Truman with a lifelong dread of abandonment and suspicion of attachment. They’re traits shared by Joel Knox in Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), who craves the love of a long-absent father who turns out to be incapable of loving him back. Joel is clearly a stand-in for Truman, a precocious adolescent (“I’m thirteen, and you’d be surprised how much I know”) with a deep, unsatisfied need for affection. At one point he prays, “Let me be loved”. But he suffers rejection on all sides, not least from his father, who listens dully when Joel reads to him. Even his words — “his métier” — fail to excite the man before him. “Other Voices was Capote’s father-dirge,” writes Schultz; “ten years later came Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the mother side of the coin.” Indeed, as Schultz points out, Holly Golightly’s real name, Lulamae, is a near-exact match of Capote’s mother’s (Lillie Mae). Holly is an altogether more complex figure, though, than Joel. She combines Lillie Mae’s “naïveté, her narcissism, her smarts, her phoniness” with much that she shares with her creator: the father-complex, the inventiveness, the “mean reds”. Her adamant rejection of meaningful attachment is all Truman, whose lifelong approach to interpersonal relations was to try to be “as invulnerable as possible”.

The second key scene in Capote’s early life was the publication (or perhaps not — so much with Truman is possibly apocryphal) of a story entitled “Old Mr. Busybody”. Capote was a resilient, thick-skinned child — and needed to be. His comportment and voice were so unlike other children’s that he was forced to develop numerous ways to deflect the unpleasantness aimed at him. One method was to turn the tables, and “Busybody” did just that: it’s a thinly veiled account of backbiting in Truman’s hometown, his neighbours his subjects. And such casual, toxic indiscretion was upsetting to the denizens of Mobile, Alabama, in much the same way that Answered Prayers would later nuke a much more powerful crowd.

“I can’t understand why everybody’s so upset,” Capote would say after the publication of excerpts from his “magnum opus” in 1975. “What do they think they had around them, a court jester? They had a writer.” More, perhaps, they had a sneak. Capote spent the ’60s and ’70s researching Answered Prayers through the cultivation of friendships with the great and good. Infamous showcases Truman in action:

But what his “sitters” didn’t know was that he planned to use their confidences for his own ends. They thought they were dealing with “a Pekinese perched on a pillow — cute, combed, pint-sized, letting out cranky yelps now and then”; in fact, he was the serpent under’t. The publication of “La Côte Basque, 1965” in Esquire was a cataclysmic event. Much more vulgar than his earlier work (though, it must be said, extremely enjoyable), it tore to pieces figures including Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Peggy Guggenheim and Tennessee Williams. Gloria Vanderbilt remarked afterwards that if she ever saw Truman again she’d spit on him. There was even a literal casualty: Ann Woodward, who, seeing herself in the caricaturish Ann Hopkins, a socialite who kills her husband (as Woodward had indeed done, however acquitted she might have been), actually committed suicide. The so-called “café society” Capote had apparently longed to belong to dropped him overnight.

Why did he do it? Motives are “more chorus than solo”, says Schultz. Answered Prayers was perhaps primarily defensive, a bizarro strategy of “preemptive abandonment. He set café society on fire in order not to get burned.” It might also have been cathartic. Schultz suggests that he used the novel to burn his mother, the source of so much of his anxiety, “in effigy”. After all, the Park Avenue set he skewered was the same set Nina Capote had so craved admission to. Or maybe Truman, who never fit in anywhere, had committed the ultimate act of “class warfare”. Whatever it was, it backfired. Despite his defiant protestations, the response to the first chapters of Answered Prayers depressed Truman deeply. His lifestyle, already chronically unhealthy, deteriorated. He stopped writing. In the end it turned out to be one of the greatest self-immolations in literary history.

Schultz’s book takes proud place alongside Gerald Clarke’s biography and George Plimpton’s oral history on the shelf marked Capote. His “pursuit of the smoking gun” is both hugely entertaining and largely convincing. The only real unanswered question (and prayer?) left concerns the mystery of how much more of Answered Prayers‘ unfinished manuscript there might be out there…